The Wayang Puppets

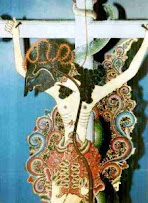

The Wayang Puppets, also just called “ the wayang “ , are made from a kind of heavy parchment of buffalo hide. The figures, which average around 50 centimeters’ tall, are tooled and most delicately perforated to outline features and dress, and then they are painted and gilded. Some of the punches used for this work are very fine; a feature, or the fold of a cloth, may be outlined by a row of tiny dots, less than a millimeter across, placed close together but not making any break in the parchment. The paint used is made from pigments mixed in a special glue so it will adhere for many years.

The arms are jointed at a shoulder and elbow, and are usually the only moving parts in a Wayang Purwa puppet.

The figures are supported and strengthened by lengths of polished horn and are manipulated by polished horn handles. The handles for each arm are attached to the hands and hang loose. But the handle for the body curves with several bends along the entire length to the head, tapering off to its thinnest part less than a millimeter in diameter in the headdress. The bottom of the elongated horn support makes a sturdy handle at least a centimeter in diameter at its thickest part below the puppet. The lowest end of the handle makes a point, which is stabbed into a banana bole to stand the puppet upright.

A complete set of wayang puppets – that is to say, sufficient characters to play the entire repertoire of the 177 plays of the Wayang Purwa – consist of about 200 figures. As many as 400, or even more, are to be found, however, in sets owned by the wealthy. Out of this number, usually no more than 60 puppets are used in a single performance.

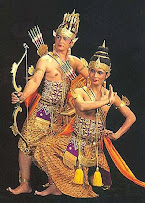

Each puppet is a highly stylized, shadow ~ like exaggeration of a type, each “personage” having a character all its own, immediately distinguishable from all others by the wayang lover. Shape of body, shape of eyes, nose and mouth, stance, dress and ornaments, all tell which of the characters is represented. Important figures in the plays ~ Arjuna, for instance ~ are even portrayed by different puppets, depending upon their mood ~ angry, or in love, say, troubled or happy. This expression of mood is called “wandha” , a term that also applies to type of character: knightly and courteous, quit and gentle, firm and brave, rough and coarse, noble and wise, sly and treacherous, merry and gay, and so forth. The characters of the puppets are long established by tradition and the puppet is made to act and to move in conformity with them.

The puppets of a collection do not consist only of heroes and heroines, villains and demons. Some puppets represent elephants, birds, horses, a chariot or an army, a shower of arrows in flight, a single arrow or club, a magical weapon ~ there are many “properties”.

There is also the gunungan , or kayon, as it is sometimes called. These are two similar tall, leaf – shaped figures that stand on either side of the action, framing the “stage”, or else are moved to the centre to indicate the end of a scene or the end of the performance. They can also be waved through the air by the dalang to indicate a storm or tumult, to show the passage of time, or a change in scene. The decoration of the gunungan is filled with symbolism of contact between gods and men. The “male” gunungan shows the forest and mountain as the dwellings of the gods and the portals below of a place of worship or of a place. The creatures in the forest are asymmetrical, that is to say, the animals on one side are different to those on the other. The companion “female” gunungan has a symmetrical arrangement of forest creatures and, instead of the portals guarded by demons that are shown on the “male” gunungan, the “female” gunungan has a stylized pond, some times with fishes swimming in it.

It would appear that the distinction between male and female gunungan is of relatively recent origin. The venerated wayang set in the Susuhanan’s Court, Surakarta, contains only one gunungan. This set is almost 200 years old.

The Ramayana is essentially a love story, the story of Lord Rama’s search for his beautiful wife, Sinta.

The Ramayana is essentially a love story, the story of Lord Rama’s search for his beautiful wife, Sinta.

The Wayang Puppets, also just called “ the wayang “ , are made from a kind of heavy parchment of buffalo hide. The figures, which average around 50 centimeters’ tall, are tooled and most delicately perforated to outline features and dress, and then they are painted and gilded. Some of the punches used for this work are very fine; a feature, or the fold of a cloth, may be outlined by a row of tiny dots, less than a millimeter across, placed close together but not making any break in the parchment. The paint used is made from pigments mixed in a special glue so it will adhere for many years.

The Wayang Puppets, also just called “ the wayang “ , are made from a kind of heavy parchment of buffalo hide. The figures, which average around 50 centimeters’ tall, are tooled and most delicately perforated to outline features and dress, and then they are painted and gilded. Some of the punches used for this work are very fine; a feature, or the fold of a cloth, may be outlined by a row of tiny dots, less than a millimeter across, placed close together but not making any break in the parchment. The paint used is made from pigments mixed in a special glue so it will adhere for many years.